“Bombardment, barrage, curtain-fire, mines, gas, tanks, machine-guns, hand-grenades – words, words, but they hold the horror of the world.” – All Quiet on the Western Front

Verdun is a small city on the Meuse River in the Alsace-Lorraine region of northeastern France.

It’s a uniquely sad, somber city.

It’s easy to understand why: Verdun’s strategic location has made it the site of numerous battles between German and French forces through the centuries.

None were larger or more tragic than the World War I Battle of Verdun, which consumed the surrounding French countryside for nearly all of 1916.

Historians estimate a combined 750,000 casualties on both sides, of which some 300,000 were killed. That’s an average of nearly 1,000 men killed every day over the course of the 300-day battle. It’s a nearly incomprehensible amount of death.

The carnage, the sadness of it, still seems to linger over the city. I did not spend a lot of time there. But what I found was atypical of Europe: instead of the lively ville vieux (“old city”) riverfront you find in the center of most towns, Verdun appeared largely lifeless.

There was little foot traffic, even on a warm spring afternoon and evening. The few bars and cafes open leaned on the seedy side. The home fronts around the downtown were shuttered and abnormally quiet. It was eerie.

Verdun, I thought, is still sad.

The true weight of the battle, one of the largest and deadliest in history, still lingers over the town.

Trenches still wind their way through the battlefield hills and forests around the city, like scars on the community that have yet to heal after more than a century. You get a chill walking through these trenches, remembering the horror that took place so long ago.

The Douaumont Ossuary is a huge haunting sanctuary housing the remains of both French and German soldiers, surrounded by a massive, largely tree-less cemetery of war dead. The starkness of the structure reflects the sad “lost generation” zeitgeist of the World War I era.

The whole scene is sad and ugly, like the war itself. The cemetery is far different, evokes a more nihilistic feeling, than the stately, reverent and dignified American cemeteries that dot Europe and elsewhere with their flowers and chapels and gleaming white marble gravestones.

The roads through the battlefields are lined with somber tombs of war heroes buried where they died; including many of them unknown soldiers (“un soldat inconnu” in French).

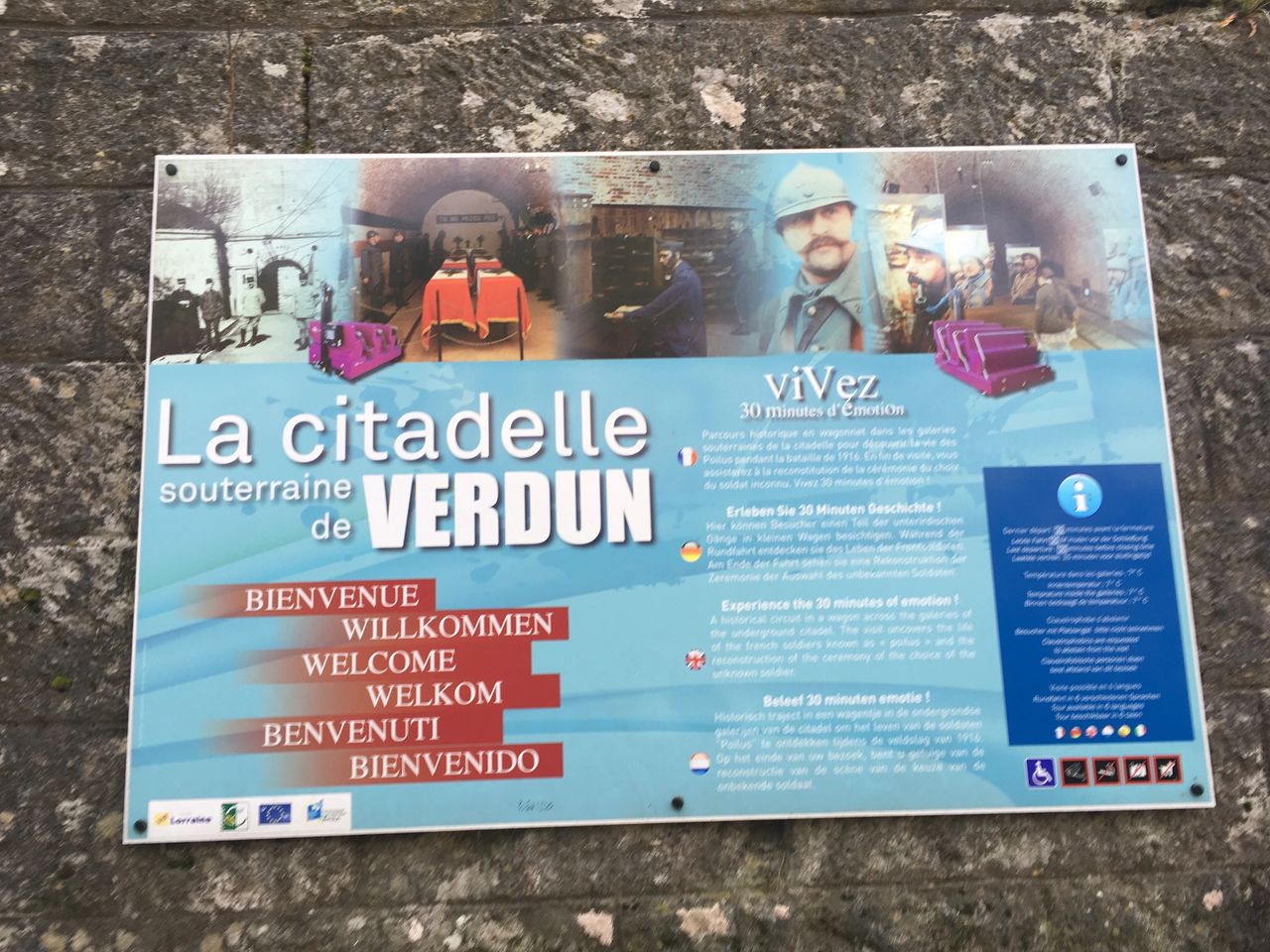

Back in the center of the city, the Citadel of Verdun is a huge subterranean fortress that served as the headquarters of the defense effort. They offer tours of the citadel via a small rail car that takes you past scenes of what it must have been like in 1916: a damp, dark, chilly space packed with soldiers, frightened civilians, the dead and the dying. Humans basically forced to live underground to survive. It must have reeked of death and human waste.

The citadel is somber and chilling today. It must have been unbelievably horrific and inhumane in 1916, just like the fields of death around it.

But Verdun, however sad, still holds a special place in the hearts and the minds of the French people. This was their Lexington & Concord, the place where their forefathers bravely held the line against a foreign aggressor on their own soil.

The French defended their homeland here at Verdun amid an unbelievably savage human toll. They stopped the German march to Paris and prevented the defeat of their country. The stalemate they created led to ultimate victory in World War I two years later – but the victory also led to a future even larger, deadlier war. Even in victory, Verdun created more sadness.

I was reminded in Verdun of the stirring and defiant words of the French national anthem, “La Marseillaise.” The song was written about another battle in an earlier era, but perhaps most fitting at Verdun.

To arms citizens

Form your battalions …

If they fall, our young heroes

France will bear new ones

A display inside the Citadel of a post-battle memorial ceremony speaks to the heroic spirit of French resistance. It bears the words On Ne Passe Pas.

“None shall pass.”

Powerful and patriotic words. But sad. Still sad. Always sad in Verdun.